The practice of herbalism often centers on community. It is an art and connection to a very old way of life, and something all of us inherently hold in our blood. It is a practice that often was connected to the sharing of knowledge, the understanding of our interconnectedness with the world around us, and being able to give and receive support and resources to and from our friends and neighbors.

Herbalism is a practice that listens to and learns from the lessons of nature, from the plants. Nature is an incredibly intelligent form of consciousness. Our natural world never wavers from the critical teachings that we must work together in order to ensure harmony and sustainability. Nature repetitively teaches us and demonstrates to us that whenever competition or the desire for power overcomes reciprocity and cohesion, failure of the system as a whole is imminent. Understanding that we are part of, not separate from, the natural world is vital and foundational to herbalism – for we cannot be sustainable if we do not understand our interconnectedness. We risk damage to the ecosystem or the loss of plant allies we hold dear. Furthermore, lack of a centering community has the potential to result in exclusion or harm to our friends and neighbors.

While it is true that such things as competition and harshness do exist in nature, at its core, nature works as a community. All beings have an important role to play in ensuring that the community continues to thrive.

We see this in the example of the forests. At one point in time, we may have once believed that trees are distinct from one another. We may have believed that trees compete against one another and that the strongest or fastest-growing will survive, shading out the weaker trees, or stealing the most water or nutrients they can out of what is available. However, Peter Wohlleben, a German forester and author of the book, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate, has done extensive research on the interconnectedness of trees and has demonstrated evidence that this previous belief may not actually be true. As pointed out in the Smithsonian Magazine article, Do Trees Talk to Each Other? author Richard Grant states, “there is now a substantial body of evidence that refutes that idea. It shows instead that trees of the same species are communal, and will often form alliances with trees of other species. Forest trees have evolved to live in cooperative, interdependent relationships, maintained by communication and collective intelligence similar to an insect colony.”

But how is this done?

Sometimes the most important inner workings of a community are those which are not visible. Similar to what we need for telephone or electronic communication, trees in a forest are dependent on infrastructure that connects them to speak to one another and share nutrients and water. This network even serves as a sort of warning system, where Wohlleben states that trees “send out distress signals about drought and disease, for example, insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive these messages.”

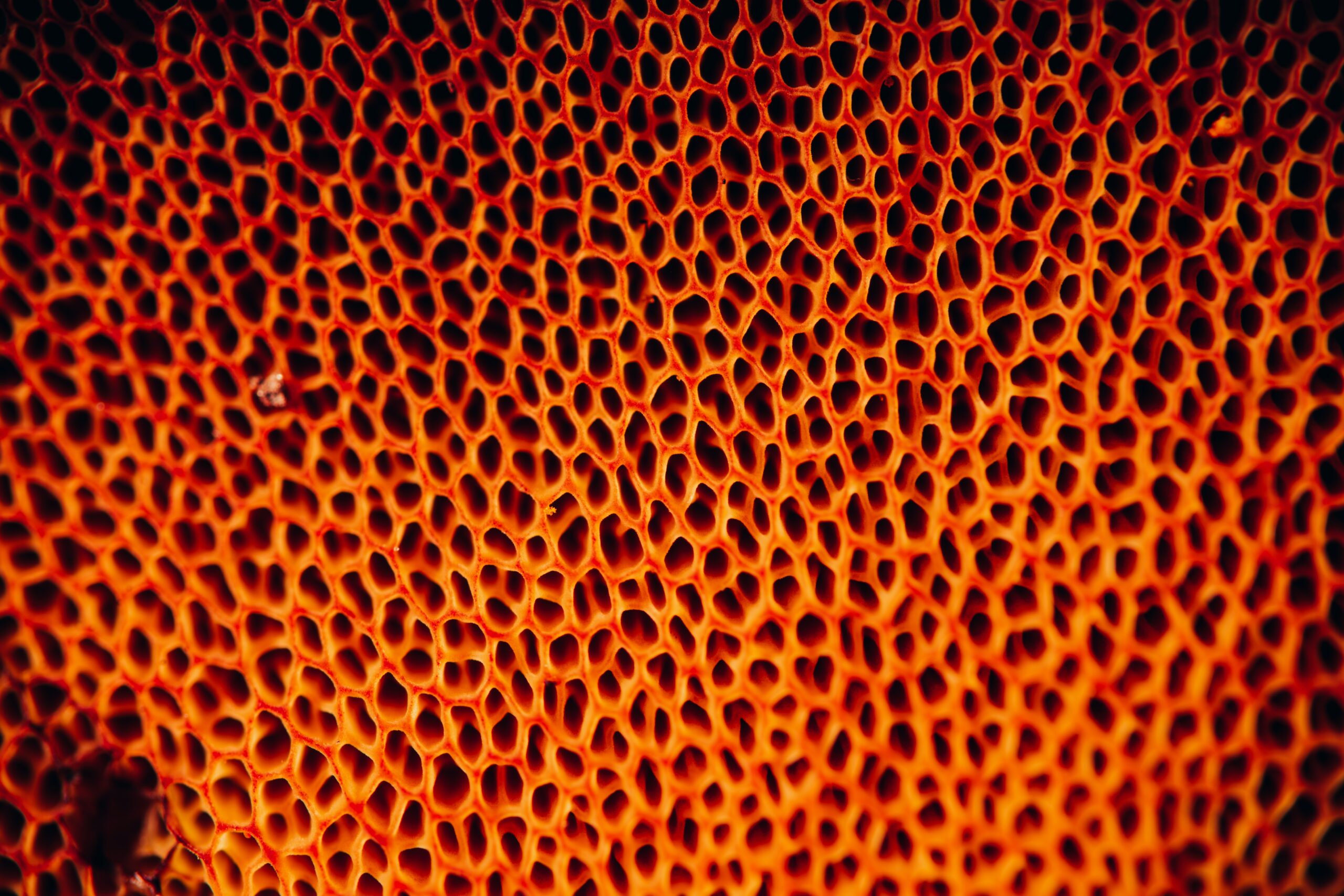

This network is created due to a symbiotic relationship the trees have with fungi. Warmly coined by some scientists as the “wood-wide web,” the network is created by microscopic fungal filaments called mycelium that form links to the root tips of trees. These networks are called “mycorrhizal networks.” In exchange for interlinking trees, so that information and nourishment can be shared, the fungi use a small amount (about 30%) of sugar that is photosynthesized by the trees. It is through this network that community support occurs, allowing trees to nourish one another and communicate needs.

Wohlleben shares an astonishing story with Grant about the community support of trees for one another:

Once, he came across a gigantic beech stump in the forest, four or five feet across. The tree was felled 400 or 500 years ago, but scraping away the surface with his penknife, Wohlleben found something astonishing: the stump was still green with chlorophyll. There was only one explanation. The surrounding beeches were keeping it alive, by pumping sugar to it through the network. “When beeches do this, they remind me of elephants,” he says. “They are reluctant to abandon their dead, especially when it’s a big, old, revered matriarch.”

How amazing is that? It was community support and love of the forest that ensured the sustainability of a single beech tree for potentially half of a millennia – done through the partnership of underground fungi.

There is also the well-known phrase for raising children that says, “It takes a village.” It is within our nature as human beings to lean quite a lot on our community when raising our children, and we have done so for many generations. This is also reflected in the forests! Young saplings, especially those growing in shady areas, as pointed out by The National Forest Foundation, are reliant upon the support of the elder trees around them. Through the mycorrhizal networks, older “mother trees” pass along nutrients, sugar, and water to their young as they grow, supporting the next generation.

Nature, through symbiotic relationships, partnerships, and interconnectedness, teaches us a lot about a thriving community. A symbiotic relationship involves all members of a party being willing to give as well as receive. Additionally, when we put our resources and love toward those who are in need of the support we can share, the community thrives as a whole. The forest teaches us that collective abundance is possible.

Being a part of a community can also help us feel seen, and being part of a culture that supports the mindset of connectedness and cohesion among neighbors can help ensure we feel less alone. Amber Magnolia Hill, herbalist and host of the Medicine Stories Podcast, paints this beautifully through an analogy referencing mycelium networks. She points out that because of the very essence of nature, we are never truly alone in this world. Ancient networks of mycelium know we are here, they absorb the energy of every step we take upon this earth. They know which direction we are moving, and share this with the natural world around us. And therefore, it is likely the community of trees we pass by, knew we were coming long before we arrived.

Perhaps when we feel alone, we can find solace in remembering that not only do the trees see us and hear us but that we are part of their community. While the mycorrhizal network supports them from below, we support their lungs through our exhalation of carbon, and that reciprocity is given back to us as we breathe fresh air into our own.

We have so much to continue to learn from the plant and fungi, and the exciting thing is that there is so much more we do not yet know. But today, we learn about how we can support the community, and we thank them for that.

We invite you to reflect with us on the guidance of nature, and what we may continue to learn by observing the interactions of the forest. While the trees do not speak verbally to us, they do still speak. What do you hear? What are they calling you to share with your own community?

We thank you for reading, and thank you for being part of our community!

Sources:

- Grant, Robert. “Do Trees Talk to Each Other?” Smithsonian Magazine. March 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-whispering-trees-180968084/#:~:text=Trees%20share%20water%20and%20nutrients,Scientists%20call%20these%20mycorrhizal%20networks.

- Hill, Amber Magnolia. Medicine Stories Podcast.

- Holewinski, Britt. “Underground Networking: The Amazing Connections Beneath Your Feet.” The National Forest Foundation. 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.nationalforests.org/blog/underground-mycorrhizal-network

Browse by category

- Aromatherapy

- Astrology & Magic

- Ayurdeva

- Botany Foraging & Gardening

- Chakras

- Digestion

- Earth Connection

- Energetics

- Flower & Gem Essences

- Folk Traditions

- Herbalism & Holistic Health

- Immune Support

- Materia Medica

- Mushrooms

- Nutrition

- Seasonal Living: Autumn

- Seasonal Living: Moon

- Seasonal Living: Spring

- Seasonal Living: Summer

- Seasonal Living: Winter

- Skin & Body Care

Don’t Miss a Thing!

Enter your email below to be the first to know about sales, new products and tips for taking care of your pieces.